Mastering Hyperscale Data Center Capacity Planning

Mastering Hyperscale Data Center Capacity Planning

In the digital age, the global economy runs on the immense computational power of hyperscale data centers. These are not merely large server farms; they are complex, city-scale ecosystems comprising hundreds of thousands of servers, distributed across millions of square feet, and consuming power on the scale of small nations. For the cloud providers, social media giants, and streaming services that operate them, a single, critical question dictates their ability to compete, innovate, and survive: “How do we ensure we have the right amount of capacity, in the right place, at the right time, without wasting billions of dollars?” The answer lies in the sophisticated, multi-disciplinary discipline of hyperscale capacity planning. This comprehensive guide delves into the intricate strategies that enable these digital behemoths to balance unprecedented demand with operational and financial efficiency, transforming what was once an IT function into a core competitive advantage.

A. The Hyperscale Imperative: Why Traditional Planning Fails

To appreciate the complexity of hyperscale planning, one must first understand the sheer scale and unique challenges involved. A traditional enterprise data center might manage a few hundred servers. A hyperscale operator, like Google, Amazon Web Services (AWS), or Microsoft Azure, manages millions.

A. The Stakes of Inaccurate Planning:

The financial and operational consequences of poor planning are monumental.

-

Under-Provisioning: A capacity shortfall means turning away customers, failing to support new product launches, and experiencing service degradation during peak demand. This directly translates to lost revenue, eroded customer trust, and a damaged brand reputation in a fiercely competitive market.

-

Over-Provisioning: Building too much capacity, too soon, is a catastrophic capital drain. Idle servers still incur costs for power, space, and maintenance without generating any revenue. This “stranded capacity” can destroy profitability and hinder a company’s ability to invest in innovation.

B. The Limitations of Legacy Forecasting Methods:

Traditional capacity planning, often based on linear projections and historical growth trends, is utterly inadequate for the hyperscale environment. It fails to account for:

-

Non-Linear, Viral Growth: A new feature or service can explode in popularity overnight, driven by global user adoption.

-

The AI and Machine Learning Boom: The computational demands of training and running large AI models are orders of magnitude greater than traditional web services and are inherently unpredictable.

-

Geopolitical and Market Shifts: Changes in regulations, entering new international markets, or a global event can instantly reshape demand patterns.

C. The Multi-Dimensional Nature of Hyperscale Capacity:

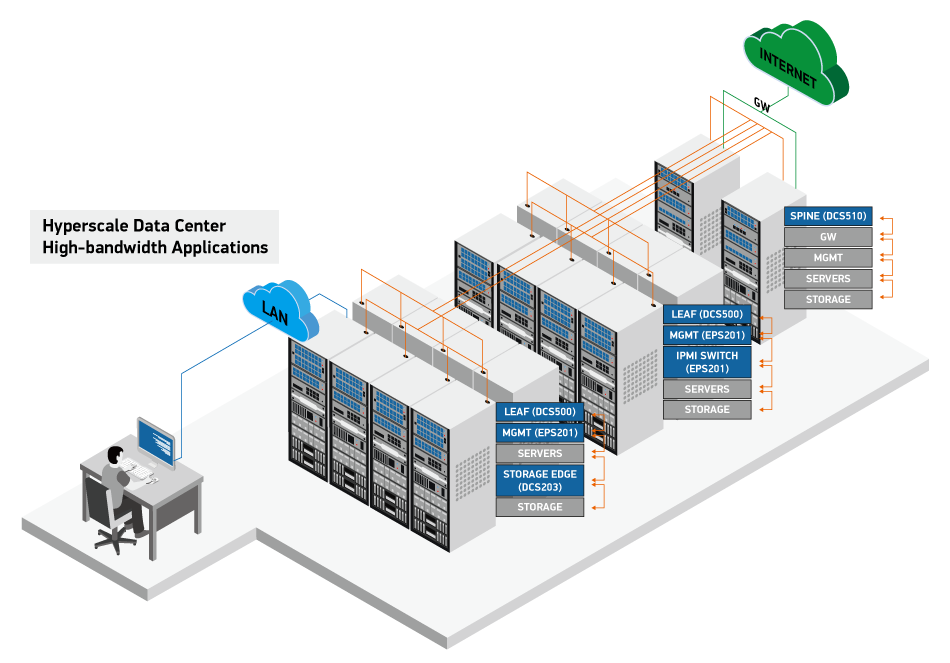

Capacity is no longer just about rack space and servers. It is a delicate balance of four interdependent resources:

-

Compute: The raw processing power of CPUs and GPUs.

-

Network: The bandwidth and low-latency connectivity between data centers and to the internet backbone.

-

Power: The electrical power required to run the IT equipment and, crucially, to cool it.

-

Cooling: The physical infrastructure’s ability to remove heat and maintain optimal operating temperatures.

A failure to plan for any one of these dimensions creates a bottleneck that renders the entire investment inefficient.

B. Foundational Principles of Modern Hyperscale Planning

Hyperscale operators have moved beyond reactive planning to a proactive, data-driven philosophy built on several core principles.

A. The Pursuit of Ultra-High Resource Utilization:

The primary goal is to maximize the workload running on every server, 24/7. High utilization directly correlates to lower capital and operational expenditure. Strategies include:

-

Workload Diversification: Mixing different types of workloads (e.g., batch processing, real-time web services, AI training) on the same hardware to smooth out demand peaks and valleys.

-

Microservices and Containerization: Breaking applications into small, isolated services that can be packed densely onto servers, increasing overall compute density and efficiency.

B. Designing for Predictable Unit Economics:

Hyperscale is a numbers game. Operators think in terms of “cost per unit”—whether it’s cost per gigabyte of storage, cost per teraflop of compute, or cost per megawatt of power. By standardizing hardware designs and data center architectures, they can achieve predictable, scalable, and constantly improving unit economics.

C. The Pervasive Culture of Automation:

No human can manually manage the provisioning of millions of servers. Every aspect of the capacity lifecycle—from hardware procurement and rack installation to software deployment and failure recovery—is automated. This automation enables speed, reduces human error, and allows for the dynamic reallocation of resources in real-time.

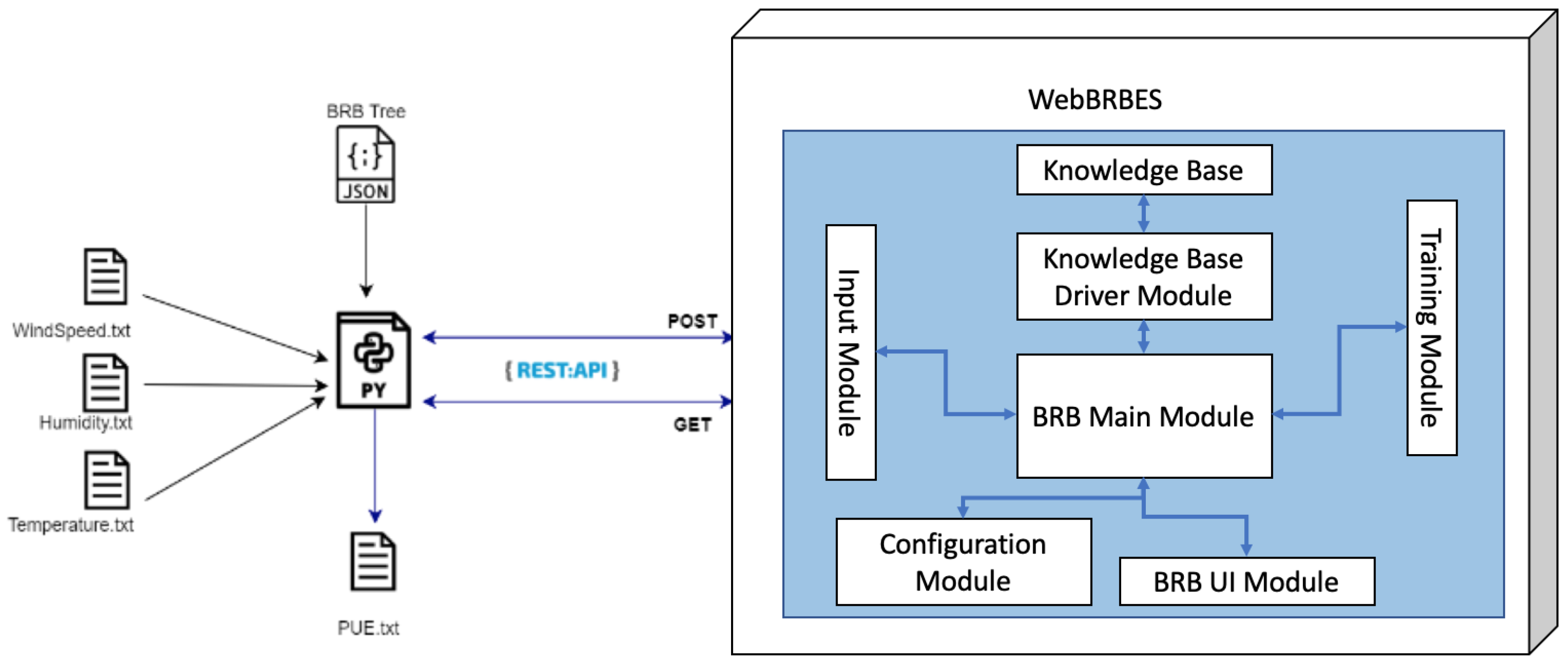

D. Embracing a Software-Defined Infrastructure:

In a hyperscale environment, the hardware is a commodity; the intelligence is in the software. Software-defined networking (SDN), software-defined storage (SDS), and orchestration platforms like Kubernetes allow operators to abstract the physical layer. This means capacity can be managed, allocated, and optimized through code, providing unparalleled flexibility.

C. Core Strategic Frameworks for Hyperscale Capacity Planning

Turning principles into practice requires the implementation of sophisticated, layered planning frameworks.

A. Predictive and Prescriptive Analytics: The Crystal Ball of Capacity:

Hyperscalers leverage vast telemetry data from their global infrastructure to build advanced forecasting models.

-

Data Sources: These models ingest data on historical usage, real-time utilization, sales pipelines, marketing campaign calendars, and even external factors like macroeconomic indicators.

-

Machine Learning Models: Using time-series forecasting and regression analysis, these models predict future demand with a high degree of accuracy, not just for the next quarter, but for the next 3-5 years.

-

Prescriptive Actions: The most advanced systems don’t just predict; they prescribe. They can recommend specific actions, such as “procure 5,000 servers of type X for Region Y in Q3” or “delay the retirement of server fleet A due to increased demand projections.”

B. The Hybrid Sourcing Model: Building, Leasing, and Colocating:

No single approach fits all capacity needs. A modern strategy involves a mix of:

-

Building Owned Data Centers: For core regions with predictable, long-term growth, building custom-designed facilities offers the lowest total cost of ownership and the most control over efficiency and design.

-

Wholesale Colocation: Leasing entire data halls from colocation providers allows for rapid expansion into new markets without the long lead times and capital outlay of building from scratch.

-

Retail Colocation and Cloud Bursting: Using smaller colocation spaces or even public cloud competitors (a practice known as “cloud bursting”) to handle unexpected, short-term spikes in demand.

C. The Hardware Lifecycle and Refresh Strategy:

Hardware is not a one-time purchase but a flowing pipeline.

-

Staggered Procurement: Continuous, staggered procurement of hardware prevents large, lumpy capital expenditures and mitigates supply chain risks.

-

Purpose-Built Hardware: Designing custom servers, networking gear, and accelerators (like Google’s TPUs) optimized for specific workloads, leading to superior performance-per-watt and cost efficiency.

-

Predictive Decommissioning: Using analytics to determine the optimal time to retire older, less efficient servers, balancing the cost of maintenance and power against the capital cost of replacement.

D. Proactive Power and Cooling Planning:

Power is often the ultimate limiting factor for a data center location.

-

Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE): The relentless drive to achieve a PUE as close to 1.0 as possible. This involves innovative cooling techniques like liquid immersion cooling, air-side economization using outside air, and using AI to dynamically optimize cooling systems.

-

Long-Term Power Procurement: Securing long-term Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) for renewable energy not only supports sustainability goals but also provides price stability and predictability for the largest operational cost.

D. The Critical Role of Advanced Monitoring and Telemetry

You cannot plan what you cannot measure. Hyperscale capacity planning is fueled by a firehose of real-time data.

A. Granular, Real-Time Utilization Metrics:

Every server, switch, and power distribution unit (PDU) is instrumented to report metrics on CPU, memory, disk I/O, network bandwidth, and power draw at minute-level intervals. This provides a living, breathing map of global resource consumption.

B. Predictive Failure Analysis:

By analyzing patterns in hardware telemetry, operators can predict component failures (e.g., hard drives, power supplies) before they occur. This allows for proactive maintenance, reduces unplanned downtime, and provides more accurate data for capacity models by accounting for planned attrition.

C. End-User Experience and Application Performance Monitoring:

Capacity is meaningless if the end-user experience is poor. Monitoring tools track key performance indicators (KPIs) like latency, error rates, and transaction times. A spike in latency can be an early warning sign of an impending capacity crunch, triggering automatic scaling actions.

E. Navigating Modern Challenges in Hyperscale Planning

The landscape is constantly evolving, presenting new and complex challenges for planners.

A. The Unpredictable Demand of AI and HPC Workloads:

The rise of generative AI and High-Performance Computing (HPC) has shattered traditional planning models. These workloads require specialized, power-hungry GPU clusters and generate immense, “lumpy” demand that is difficult to forecast. Planners must now create separate, agile strategies for this “AI capacity.”

B. Global Supply Chain Volatility:

The just-in-time hardware delivery model is vulnerable to global disruptions, as seen during chip shortages and logistics bottlenecks. Strategies now include holding larger safety stocks of critical components, diversifying suppliers, and designing for component flexibility.

C. Sustainability and Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Mandates:

Hyperscalers are under immense pressure to reduce their carbon footprint and water usage. Capacity planning must now integrate sustainability goals, favoring locations with access to renewable energy and investing in technologies that reduce water consumption for cooling (Water Usage Effectiveness or WUE).

D. Data Sovereignty and Regulatory Compliance:

Laws requiring that data about a country’s citizens be stored and processed within its borders (e.g., GDPR in Europe) force a distributed capacity model. Planners must build smaller-scale capacity in numerous regions, which can be less economically efficient than concentrating it in a few mega-centers.

F. A Step-by-Step Framework for Effective Capacity Planning

While each hyperscaler has a proprietary process, the general framework can be broken down into a cyclical, multi-stage approach.

A. Stage 1: Data Collection and Baseline Establishment:

-

Aggregate data from all monitoring systems, financial forecasts, and product roadmaps.

-

Establish a clear baseline of current utilization, capacity headroom, and performance metrics.

B. Stage 2: Demand Forecasting and Modeling:

-

Run predictive models to generate short-term (0-12 months), medium-term (1-3 years), and long-term (3-5+ years) demand forecasts.

-

Model different scenarios, including “worst-case,” “best-case,” and “most-likely” outcomes.

C. Stage 3: Gap Analysis and Risk Assessment:

-

Compare the forecasted demand against current and planned capacity.

-

Identify potential gaps (shortfalls) and surpluses.

-

Assess the risks associated with each gap, including financial, operational, and reputational impact.

D. Stage 4: Strategy Formulation and Investment Planning:

-

Develop a multi-faceted plan to address the identified gaps. This could involve:

A. Building: Initiating the design and construction of a new data center (2-3 year lead time).

B. Leasing: Signing a contract with a colocation provider (6-18 month lead time).

C. Optimizing: Reallocating existing resources, improving utilization, or retiring inefficient hardware. -

Create a detailed capital and operational expenditure budget.

E. Stage 5: Execution and Continuous Monitoring:

-

The procurement, construction, and deployment teams execute the plan.

-

Continuous monitoring systems track progress against the plan and flag any deviations in real-time.

F. Stage 6: Review and Optimization:

-

Conduct regular post-mortem analyses on the accuracy of forecasts and the effectiveness of the plan.

-

Use these insights to refine models and improve the planning process for the next cycle.

Conclusion: The Strategic Engine of Digital Dominance

Hyperscale capacity planning has evolved from a technical back-office function into a core strategic discipline that sits at the intersection of finance, engineering, and business strategy. It is a continuous, dynamic dance between anticipating the future and managing the present. The companies that master this discipline—through deep data analysis, strategic foresight, relentless automation, and agile execution—are the ones that can reliably deliver the instant, global, and scalable digital services that the modern world demands. In the race for digital supremacy, robust and intelligent capacity planning is not just an advantage; it is the fundamental engine that powers growth, innovation, and market leadership. As we move into an era dominated by AI and an ever-more-connected globe, the strategies for planning the infrastructure to support it will only become more critical, complex, and decisive.